I was in a meeting the other day and a question came up about the purpose of the Visual Studio Task List. A couple of the developers had never used it before, so I thought it’d be a good topic for the blog.

![]()

The Task List, by default, appears in the bottom left window pane of Visual Studio (the same place where build errors and warnings appear). Alternatively, you can find it under the View menu. Microsoft provides some basic documentation on the Task List feature here. However, the documentation glosses over some developer best practices, so I thought I’d expand on that a little.

NOTE: Before I go further, I want to preface everything by saying that the task list should not replace more robust issue tracking systems, like TFS Work Item Tracking, Microsoft Project or another 3rd party product backlog or issue tracking solution. That being said, the Task List can be beneficial in defining more granular programming tasks that may not be appropriate in a higher-level work tracking system.

Code Comments vs. User Tasks

Two types of tasks can be captured in the Task List pane: User Tasks and Code Comments.

User Tasks provide generic notes that a developer may want to remember during development. They work pretty much like Outlook Tasks do, except without any of the features that make Outlook Tasks useful. After about five minutes, you’ll quickly realize just how limited User Tasks are. I usually stay away from them because

- Most of what I have used them for, I should be putting in an Issue Tracking / Work Item Tracking system.

- User Tasks are not stored in version control; therefore, other developers cannot see them and I lose them if I ever move or delete my local working environment.

Let me spend a moment longer on that last bullet, because I think that’s an important point.

User Tasks are stored in the developer’s *.suo file, which is not stored in source control by default (nor should it be). The *.suo file contains user-specific preferences, such as the state of the Solution Explorer, which should not be shared across developers. When another developer opens a solution for the first time, a new *.suo file will be created automatically.

This leads us to Code Comments, which are much more useful. Code comments are literally comments in your code (hence the name) that have been prefaced with a pre-defined keyword. Creating code comments is a very straight-forward activity:

'VB.NET

Try

'some code here

Catch ex as Exception

'TODO: Need to implement roll-back feature in transaction.

Throw

End Try

// C#

Try {

// some code here

}

Catch ex as Exception {

//TODO: Need to implement roll-back feature in transaction.

throw ex;

}

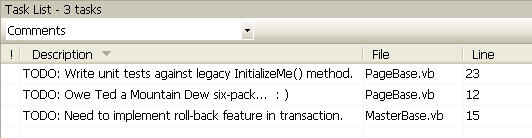

By preceding a comment with “TODO”, it automatically appears in the Task List. As you can see below, it is possible to see all code comments within your project/solution at once:

Task List pane with all-important programming tasks

Code Comments improve upon User Tasks in a variety of ways. For example, code comments allow you to “bookmark” your code in case you need to come back to it later for refactoring or a re-design. Also, code comments are in source code. Source code is stored in version control and shared among the development team. See where I’m going with this?

I hope this helped shed some light on another little feature of the Visual Studio IDE.